173 – Indirect influences of policy on environmental outcomes

There are many policy programs around the world that aim to influence the activities of farmers in order to benefit the environment. Sometimes people fall into the trap of thinking and talking about these programs as if they were mechanistic in their impacts on the environment — you pull a policy lever and get an outcome. Of course, the reality is not that simple. The influence of policy actions on the environment is indirect and compromised by other factors, making life rather difficult for policy makers who wish to achieve particular outcomes.

The difficulty is that, in practice, in a democracy it is not in society’s power to select a particular sustainable farming system, because the government cannot simply order farmers to adopt the chosen system. Rather we are constrained by the effectiveness of the various tools that can be used to encourage adoption of different practices. The farming system that comes into existence will be that which results from farmers’ reactions to the government policies and institutions in place, allowing for other constraints and considerations.

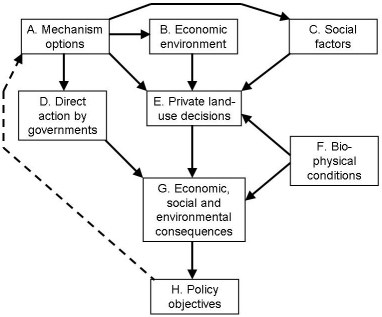

Figure 1 illustrates these ideas. It shows that an environmental body (e.g. government agency, Catchment Management Authority, or NGO) concerned with land use can influence the decisions of private landholders (box E) through the selection and application of policy mechanisms (box A). The mechanism options include things such as regulation, education, subsidies, conservation tenders and research. The figure highlights that the environmental body is only one of a number of broad influences on land-use decisions, others including the economic environment, social factors, and bio-physical conditions. Clearly, the ability of environmental bodies to control land use is partial and often highly uncertain.

Figure 1. The indirect and partial effect of policy (through choice of policy mechanisms – box A) on land use and natural resource outcomes.

Actual land use has a set of economic, social and environmental consequences (box G) which may or may not align with the objectives of the policy maker (box H). If they do not, the environmental body can attempt to improve the alignment by modifying the policy mechanisms being used (link back to box A).

An alternative route to achieve policy objectives is for the body to undertake required works itself (box D). For example, governments may choose to establish national parks, to repossess private land in order to alter its management, or to implement engineering works to protect environmental assets.

Science may influence land use through several channels. These include giving landholders better knowledge of the relevant biophysical or economic conditions (boxes F and B) and their influence on outcomes from different land uses; through developing improved technologies that provide new land-use options (altering the influence of box E on box G), or indirectly through better informing policy makers.

Note that land-use change is occurring continuously, irrespective of policies or science, as a result of changes in economic, social or bio-physical conditions or changes in technology. It may also occur as a result of other policies that are not intended to target land use, such as taxation or trade policy. Overall, the influences of policy and science are complex, and often indirect.

A lot of environmental modelling doesn’t do justice to the complexity of this system. Economists are better than most in this regard. There are at least some numerical models that represent policy mechanisms affecting farm business decisions, flowing through to environmental consequences (e.g. Doole, 2010). Another relevant approach is the ‘Principal Agent Model’, which explicitly represents the relationship between a principal (such as a government) and agents who the principal wishes to influence (such as farmers). These models are used to design policy mechanisms that will achieve the optimal balance between benefits and costs, given different objectives and different information levels between the principal and the agents. When applied to the environment, they typically involve only a simplistic representation of the biology, but they do at least represent the human behavioural aspects of the system explicitly.

David Pannell, The University of Western Australia

Further reading

Doole, G.J. (2010). Evaluating Input Standards for Non-Point Pollution Control under Firm Heterogeneity, Journal of Agricultural Economics 61, 680-696.

Pannell, D.J. 2003. Balancing economics and sustainability in building an integrated agricultural system, Pacific Conservation Biology 9 (1/2), 23-29.

Pannell, D.J. and Roberts, A.M. (2009). Conducting and delivering integrated research to influence land-use policy: salinity policy in Australia, Environmental Science and Policy 12(8): 1088-1099. Full paper (94K) – Journal version on-line

this post is very good and its all about how the policy or any other practice can influence the environmental outcomes and this is very important for us and also for the farmers that how all these practices can have an effect on the environment. Its not all about who implemented the policy but no one can force a farmer to take that policy rules and regulations because a farmer’s point of view is very important and need to be taken in consideration. From my point of view a farmer can only understand which policy or practice is useful for our environment.