291 – The Swinford Toll Bridge

In some countries, tolls are collected on particular roads or bridges. I recently saw a remarkable example, with a fascinating history, near Oxford.

Last week I completed a 180 km walk along the bank of the River Thames in England. It was absolutely gorgeous, with numerous points of beauty, lots of great historical stuff to look at, and some surprises.

One of the surprises was the Swinford Toll Bridge, near the town of Eynsham, just upriver from Oxford.

A small toll booth collects 5p (about 10 cents) from each car that crosses the bridge. Tolls have been collected here since the bridge was opened in 1769. It hardly seems like it would be worth the bother of collecting 5p, but there is plenty of traffic crossing the bridge, so it collects around £200,000 per year.

Clearly, the charging of tolls is not a new thing. In fact, there were a lot of toll roads and toll bridges in England in the 18th and 19th centuries. According to the World Bank, most countries currently have no tolls, but tolls do continue to be created and/or maintained in some countries, including Australia. There are various possible rationales for imposing tolls, including the following.

- To generate revenue for the government, allowing reductions in other taxes.

- To charge actual users of the road or bridge (consistent with a “user pays” philosophy), reducing the burden on taxpayers who happen not to use it.

- To discourage use of the road or bridge by creating a price for its use. This may help to reduce a problem, such as congestion or noise, by encouraging use of public transport or use of different routes.

- To encourage private-sector funding of infrastructure by allowing the funder to recover their costs through charging a toll.

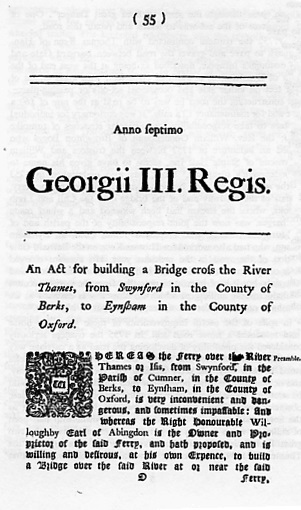

In the case of the Swinford Toll Bridge, it was that last rationale that led to the toll. In the mid 1700’s there was a desperate need for a good bridge in the area, particularly to allow farmers to deliver their produce to Oxford for sale. The government was not forthcoming with funds, and taxing the local community to collect funds to pay for construction of a new bridge was specifically ruled out by a clause in the Magna Carta!

To the rescue came the Earl of Abingdon, who agreed to pay for construction of the bridge. He had more than one motivation for putting up the funds. One was that he owned farm land in the area and would benefit himself from better access to the Oxford market.

The other was that he was promised extremely favourable conditions, consisting of:

The other was that he was promised extremely favourable conditions, consisting of:

- The right to charge a toll, including on pedestrians;

- The right to exclude any other bridges from being built within 3 miles (5 km) of the bridge, creating a local monopoly;

- Freedom from the requirement to pay any taxes on the tolls collected;

- Ownership of the bridge and its tolls to be passed to his heirs and to continue forever.

What a deal! This was all enshrined in an act of parliament, which is still in operation.

Some things have changed since 1769. The toll has gone up in nominal terms (without adjusting for inflation) but fallen in real terms (allowing for inflation), pedestrians no longer have to pay it, and the Earl’s descendants sold the bridge to an investor.

I’m not sure how many times it has changed hands, but most recently it was sold for over £1 million in 2009. Other than that, things carry on essentially unchanged for this beautiful bridge with its quaint toll.

Not surprisingly, some of the local residents are not happy about it. It was immediately obvious to me that paying the toll results in long queues leading up to the bridge, especially at peak times.

The resulting frustration, loss of time and the cost of petrol consumed while queuing would be far more significant to local people than the need to pay a tiny toll. For over a century, locals have been trying to get rid of the toll. When the bridge was for sale in 2009, they wanted the Oxfordshire County Council to buy it and abolish the tolls, but this didn’t happen. It may be a long time before there is another opportunity.

The resulting frustration, loss of time and the cost of petrol consumed while queuing would be far more significant to local people than the need to pay a tiny toll. For over a century, locals have been trying to get rid of the toll. When the bridge was for sale in 2009, they wanted the Oxfordshire County Council to buy it and abolish the tolls, but this didn’t happen. It may be a long time before there is another opportunity.

It seems to me that the original reason for allowing private ownership of the bridge was OK, but that the conditions offered were too generous and too permanent. Conditions have changed greatly since the act of parliament (cars!), resulting in large unanticipated costs to the current community. It’s always difficult to anticipate what costs a new law or regulation might generate, especially 250 years in the future.

Further Reading

Hyman, G. and Mayhew, L. (2008). Toll optimisation on river crossings serving large cities, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 42(1), 28-47. IDEAS page

Dave

I remember paying a toll on a pedestrain footbridge, also across the Thames but downstream near Richmond, to get to Eel Pie Island. As a young woman I used to take the footbridge to access the rock shows that featured at Eel Pie Island on a Saturday night in the sixties, to hear bands like the Rolling Stones before they got big.

If this was based on a similar historic arrangement the kiosk must still be there.

Thank you for kindling this distant memory, and for your insights on the use of tolls as a public policy.

Chrissy Sharp

I’ve heard of Eel Pie Island and those rock shows! What a great memory to have.

Dave I crossed that pedestrian bridge to Eel Pie Island just a few weeks ago! Definitely no toll now, but instead there are signs trying to discourage non-residents from crossing!

Great story. Swinford bridge is not alone: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitney-on-Wye_toll_bridge . Constructed in 1797 with similarly generous terms through an Act of Parliament that inluded treating the toll income as tax free.

Best wishes

Ben