363. The Beatles: Get Back

Peter Jackson’s documentary masterpiece, The Beatles: Get Back, was released in November. I know that thousands of people have already commented on it, either in text or video, but some friends have asked me to share my thoughts, so here goes.

For anybody who hasn’t been paying attention, The Beatles: Get Back is an eight-hour documentary series about The Beatles’ rehearsals, recordings and final live concert in January 1969. Film of the month’s work was originally released as the movie Let It Be in 1970, but that was edited in a particular way and, lacking any story arc, it left viewers thinking most about intra-group tensions and disharmony. It shaped people’s views about what had happened in that month, seemingly including the views of The Beatles themselves.

Now, Peter Jackson, a devoted and extremely knowledgeable Beatles fan, has been given access to the original footage and audio, and he has done something remarkable. Although the eight-hour version doesn’t hide any of the tensions (in fact it is even more open about them), seeing them in this much more expansive format completely transforms how the viewer feels about them. We now see more clearly the deep bonds of respect and affection between the Beatles, and we also see their creative process in incredible detail. Although, they start with what seems like an impossible goal – write, learn, and record live a new album in two weeks – and we see them drifting apparently rudderless and a wasting lot of time, at the end of the month they have pulled it off.

Somehow, this is one case where knowing the punchline doesn’t detract. The program is emotional, inspiring, exciting and quite unique. It is far, far better than fans hoped it would be, or even imagined it could be. It is clear from the commentary and social media that it is also engrossing viewers with only casual interest in The Beatles, and it’s creating a lot of new fans. Before it was released, The Beatles were still selling more albums than any other group in the world, even 50 years after they broke up, and this will only widen the gap.

There have been numerous great articles written about it already (my favourites are here, here and here), so I’m just going to focus on a few issues that stood out to me.

Time pressure and productivity

As I said, The Beatles’ aim was to write and record a new album in two weeks. That seems completely nuts. Why would they even go into a project with an aim as crazy as that?

Actually, it was even more outrageous than that, for reasons that Get Back doesn’t cover. When they started work on January 2, 1969, it was only 10 weeks since the last session for The White Album, their brilliant double album, and incidentally my favourite album of all time. It was only five weeks since that album had been released and it was ensconced at the top of the charts all over the world. In addition, their single, “Hey Jude”, had been in the charts for four months and would remain there for another month. So there was absolutely no need to rush into doing their follow-up album.

And it’s not as if they had used those few weeks since finishing The White Album to get a head start on writing the songs for the next album. John and George, in particular, were far too busy for that. For example, during that period George devoted most of his time to producing an album for a Liverpool singer named Jackie Lomax. Apart from that, he spent time in the US playing with and hanging out with Bob Dylan and The Band, he released an experimental album called Electronic Sounds, he appeared on a TV comedy show in the US, and he played on the recording of the song “Badge” by Cream (with Eric Clapton). Not a lot of time for writing songs for the next Beatles album, then.

John and his girlfriend Yoko Ono released their first experimental album, Two Virgins, to great controversy due to them appearing naked on the cover. Yoko became pregnant, but there were complications and she eventually suffered a miscarriage. They spent some of her time in hospital recording their second experimental album, Life with the Lions. They also appeared together on the Rolling Stones’ TV special, The Rock and Roll Circus. In the middle of all that, John’s divorce from his previous wife Cynthia was finalised, and John and Yoko were busted for drugs and appeared in court. Clearly, he’d have had no time or head-space for song writing.

Paul was less frantically busy: he had holidays in Scotland and New York with his girlfriend Linda Eastman and he spent some time promoting The White Album.

Ringo seems to have rested; very sensible.

Given all that, aiming to start and finish an album in January seems beyond crazy. Except that it wasn’t. They knew they could do it, because they had done something broadly similar multiple times before. Indeed, believe it or not, five of their previous albums had been written and recorded under comparably extreme time pressure. With The Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles For Sale, Help! and Rubber Soul were all done with extraordinary efficiency, in almost no time, crammed in between an incredible intensity of commitments including concert tours, interviews, photo shoots, functions, making radio shows, making movies, travel, and everything else they did, with hardly an hour off. Starting in 1966 they took a lot more time over their recordings, and in the process revolutionised the whole process of recording music, but they knew they could do it incredibly quickly if they tried.

Admittedly they did take four weeks rather than two, but one of those weeks was downtime due to George temporarily quitting the band and them moving to a new recording studio that wasn’t finished. And by the end of the month, not only had they done the recordings for Let It Be, but they had written most of their next album, Abbey Road (11 of the 15 tracks), and about 12 songs that ended up on their solo albums. It’s completely ridiculous. How is that even remotely possible? Some of those extra tracks were hanging around from the White Album era, but even so it beggars belief.

And it’s not as if this flood of songs meant that quality was compromised. It includes some of their best songs, which means it includes some of the best songs ever created.

Creativity

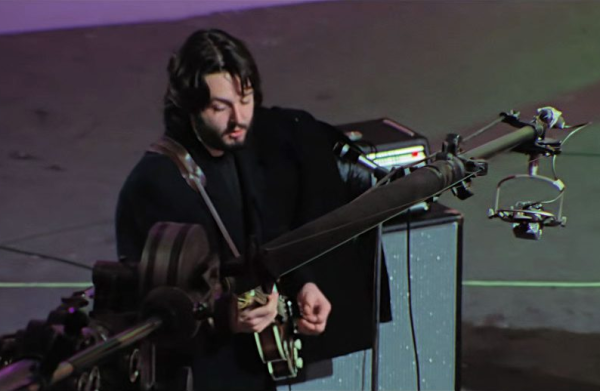

The program is a wonderful laying bare of The Beatles’ creative processes. This is a continuous joy throughout, but the highlight is the song “Get Back” for which we see almost every aspect of its creation and development. We see Paul come up with the chords and melody of the verse when he’s strumming his bass (strumming!) while waiting for John to arrive one morning. Almost immediately a bunch of the song’s words tumble out and then he spontaneously sings the chorus, “Get Back”.

George and Ringo witness this, and they recognise straight away that it’s good and start to play along. Up to this point it’s been all inspiration, no perspiration. Almost the entire song just spontaneously appeared out of a clear blue sky in almost no time. (Paul has confirmed that he wasn’t building on any prior ideas – what we see is genuinely the instant of creation.)

A couple of days later, they experiment with changing the theme of the song to make it more-or-less a protest song against racism in British politics, but that doesn’t really work, so they go back to the original theme.

Later again, we see Paul and John working on the lyrics together. This is intriguing because it makes it clear that the song is not really about anything. They search around for words and phrases that fit the melody line and seem consistent with the random theme that Paul first came up with, but there is actually no real meaning or message to them. The music is by far the more important thing for them, at least in this song.

During the protest-song phase, they play it in a couple of different ways with very different arrangements, one mid-paced and one fast. In the mid-paced one, Paul does lots of vocal howling, and in the fast one, Paul and John sing all the words in unison (not in harmony), but neither of these versions really works, so they abandon them. After Billy Preston joins the sessions, they settle on the arrangement we know and love, with Ringo’s unusual drum pattern emphasising the on beat, Paul’s simpler than simple bass lines, George’s chugging rhythm guitar, John, surprisingly, playing lead guitar, and Billy playing electric piano.

The song has an unusual structure, with only two sung verses, three instrumental solo verses (two by John, one by Billy Preston), two different versions of the chorus, and a bit where it winds down to a break mid-song and near the end, and we see them batting around ideas about how these different elements should be sequenced.

A few days before the roof-top concert, we see them rehearsing the completed arrangement of the song, and we see them making numerous attempt to record a releasable version. Finally, they play the actual version that was released as a number 1 single, although they don’t realise at the time that they’ve nailed it. (Actually, the released version was an edit of two takes.)

The moment of first creation has attracted the most attention from commenters, and it’s true that it’s thrilling to watch, but the rest of the creative process is also fascinating and just as important to the final version of the song.

Something a bit similar is happening with most of the other songs too, but “Get Back” is the only one for which we see it all from initial spark to completion. It’s probably the only number 1 hit in history whose entire creation has been captured in this way.

It’s also notable that all this creativity happens in a room crowded with people (the filmmakers, the band’s support staff, and various others) who are not part of the band. It amazes me that they can shut that all out and be as creative as they are.

Personalities

The program reveals a lot about the four Beatles, their personalities and relative strengths and weaknesses. I read one comment that said it could be used as a training course to prepare people for intense teamwork. Not that they get all of the team process right – far from it – but they get enough right to make it work, and the bits they get wrong are informative too.

The differences in their personalities really stand out. Most strikingly, Paul is the organised one, the driver of the ship, the one constantly (relentlessly, unstoppably) coming up with creative ideas, most of which are good. Paul has clear and detailed views about the arrangements for his songs, and he provides a lot of instructions to his bandmates. That seems to be fine with John and Ringo but grates on George.

Despite Paul’s energy, John is still the leader, and Paul often seeks his approval. (But John also seeks Paul’s approval and input at times.) Interestingly, John’s leadership style is quite passive. He gives few directions, even about his own songs, but it’s clear that he is first amongst equals. In the first episode, covering the first week of rehearsals, he is clearly high for part of the time. He is probably on heroin, which he and Yoko were both using at that time. To some degree, this might be explained as self-medication following the loss of their baby and their recent drug bust, but on the other hand, he had always taken a lot of drugs. In the second and third episodes, he seems clean and is fully engaged, but his productivity of new songs remains the lowest of the three. I suspect that him being so totally overshadowed by Paul in providing the best songs for this album was one of the reasons why John later did not recall the sessions fondly.

There are two different versions of George on display. In the first episode, he is clearly not happy, and his tolerance for Paul’s instructions is low. The documentary doesn’t tell us this, but George was going through a very difficult time that week. His marriage was breaking up, largely caused by his own infidelity. He had also just spent time in the US being highly praised and respected by Bob Dylan and members of The Band, so he may have been contrasting that experience with his relatively low status within The Beatles, particularly John and Paul’s failure to recognise that George’s songs were getting stronger and stronger. He did comment on that later in various interviews. The culmination of his unhappiness was that he quit the band after a week of rehearsals. It took most of a week for the others to convince him to re-join, but when he did, he seemed much happier and much more engaged. Having Billy Preston join the band at that point may have helped.

Finally, Ringo is the ultimate team player. His role is to support the others’ songs, and he does it brilliantly. He is generally the first to have his part for a new song worked out, and it is always perfect for the song and flawlessly performed. I saw a nice tweet after the final episode had aired saying that people who liked to criticise Ringo must be feeling pretty embarrassed.

Relationships

One of the most interesting aspects is watching the relationship between John and Paul. They are constantly looking at each other and feeding off each other. It’s quite intense. It’s easy to see why George felt a bit pushed out.

One of the issues highlighted by Peter Jackson in his promotion of the series is that the sessions were a lot more positive and friendly than came through in the original Let It Be movie. This is definitely true. Notwithstanding George’s problems, there is a constant stream of joking and banter. Even in the midst of a heavy discussion where George and Paul raise the possibility that the band could get divorced, John pipes in with “Who’ll get the children?”, to which Paul’s immediate and brilliant response is “Dick James”, their song publisher. Especially after George rejoins (episodes 2 and 3), there is a lot of playfulness. They also spend a lot of time jamming on old songs, sometimes their own songs but more often old rock and roll songs from the 1950s. This was just about having fun and getting tighter as a group.

Related to that, there is quite a bit of nostalgia on display. They have fun playing a bunch of very early Lennon-McCartney songs from the 1950s that pre-date the time when they were even gigging regularly. These have titles like “Because I Know You Love Me So”, “I Fancy My Chances With You” and “Too Bad About Sorrow”, and they are as lame as those titles sound. But that’s fair enough: they were written by Paul and John when they were 15/16/17 years old. In their conversations, there are numerous references to their pre-fame days, especially their time in Hamburg (they made five trips there in 1960-62).

I find this really interesting. Here is a group who were responsible for transforming the entire music industry on so many fronts: the expectation that musicians would do their own song writing, creative use of the recording studio, the nature of concert touring, ramping up the artistic status of albums, etc., etc. They could look at a long list of towering achievements, and reflect on their huge influence on the world. For the five years up to January 1969 they had been the four most famous people on the planet. And yet, when they reminisce, they don’t talk about any of this, just their pre-fame days.

Maybe it’s just that the earlier times were more fun. Heaven knows the pressure on them, and the workloads required, would have crushed most people. My earlier observation that they had the equivalent of two weeks to write and record about half their albums is indicative of this, but this sort of pressure applied to every aspect of their working life. They were well aware of their achievements, and they were immensely proud of them, but the whole process must have been like going through a tornado.

Notably, they went through the tornado together. They were the only four people (in history, really) to go through that experience, and it was a shared experience with a strong flavour of four against the world. Combining that with the fact that John, Paul and George had known each other since their mid-teen years, it is no wonder their relationships were so tight. (Mick Jagger called them the four-headed monster.) This is why they could work together so effectively despite the challenges.

Overall, The Beatles: Get Back is amazing. It’s probably too early to tell, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it is ultimately assessed as belonging in the top rank of Beatles outputs, along with Abbey Road, The White Album, Sgt. Pepper, Revolver, Rubber Soul, “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane” and various other singles, and the A Hard Day’s Night movie. I’ll be re-watching it regularly.

p.s. 23 January 2022. I just finished rewatching the series again, and I’m moved to add one more observation: what a fantastic live band they were! Once they get on the roof, even though they are extremely out of practice in terms of live performance, they lock in and do an amazing job. It’s spine-tingling.

Recommended podcasts

Here is a selection of podcasts discussing Get Back in-depth, each presented by extremely well-informed Beatles experts.

Something About The Beatles (SATB): episodes 224A, 224B and 224C provide a long and hugely interesting interview with director Peter Jackson covering all aspects of making The Beatles: Get Back.

Nothing Is Real: Season 5, episode 10. A great discussion of the series. The two presenters, both Irish, are hugely entertaining to listen to, and their depth of knowledge of the Beatles is extraordinary.

The Beatles Naked: Episodes 35, 36 and 37. Each of these three podcast episodes covers one episode of the series. They were broadcast almost in real time – the day after each episode – so they convey initial reactions.

If you really want to get into the fine details of The Beatles’ work in January 1969, the podcast for you is Winter of Discontent. This is progressively playing every minute of the available audio recordings and providing explanations, commentary and context. I’m enjoying this a lot more than I enjoyed plowing through all 75 hours of the sessions that I could get.

Simply superb as ever – I agreed the hell out of it so it must be right!

Loved the understatement in: “It includes some of their best songs, which means it includes some of the best songs ever created.” Most of all I share the feeling regarding the capture of the creative process yielding the title song Get Back. Watching that for the first time was an experience I don’t think I will ever forget – magnificent

Hi Dave. I’ve been waiting for this piece from you after your prior excellent posts on the Beatles and music. Excited to see it this morning. I was a casual Beatles fan, watched Get Back and now am listening to a lot of their albums, informed by your ranked post (https://www.pannelldiscussions.net/2018/01/beatles-albums-ranked/). Really loving the music and loved the series – have rewatched the Get Back song creation many times. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Brilliant. Cheers

Good one Dave. I recall a friend saying to me in ’69 that this is classical music: people will still be listening to it 100 years from now. We are past the halfway mark.

Hi Bruce, yes, I’ve been thinking about that. There are so many devoted Beatles fans now who weren’t even born when they were making their music, it really does look likely that they will be around for a long, long time. One article about Get Back said, if you don’t like The Beatles, don’t worry, the fuss will die down in a few centuries.

Very interesting, thanks David. I remember the precious Beatles album that was played, alongside the Shadows, Cliff Richard, Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan (acoustic only) day after day in the students’ common room at school. Sure, they will become classics. You don’t have to have violins to make a classic.