400. The Journal of Beatles Studies

Last year a new research journal was established, The Journal of Beatles Studies. I decided to try to get a paper published in it.

I have succeeded! I can hardly express how excited I am about this. Nothing I’ve ever published before has gone close to making me feel this happy about a new research paper.

Long-term readers of this blog know of my passion for the Beatles (see PDs 363, 311, 293, 264, 225, and 10). As I look around my home office, I can see my huge Beatles collection including several hundred of their records and CDs (together and solo, official and bootleg), dozens of video items on various types of media, about 100 books, many magazines, and much memorabilia. I still play their music pretty much every day and I’m always reading, watching or listening to something about them. I believe my obsession is healthy; they are a source of great joy in my life.

So it was quite a buzz to find them sort of crossing over into my professional world, in the form of a new research journal. The Journal of Beatles Studies was announced by the University of Liverpool last year, to much media attention, and it published its first issue later in the year.

So it was quite a buzz to find them sort of crossing over into my professional world, in the form of a new research journal. The Journal of Beatles Studies was announced by the University of Liverpool last year, to much media attention, and it published its first issue later in the year.

The Beatles are the biggest-selling musical act of all time. No other rock music act has had anything like their influence on other musicians and the music industry. In addition, they probably have had the greatest socio-cultural impacts of any musicians in history. This is reflected in the huge and remarkably diverse body of research literature about them, including studies of: particular songs and albums, their compositional techniques, their lyrics, their movies, their aesthetic appeal, their influences in various countries, their contribution to cultural globalisation, their place in history, Beatles tourism, Beatles fandom, the Beatles and the media, the Beatles and politics, the Beatles and religion, the Beatles and the law, the Beatles and masculinity, and studies that link them in some way to biology, technology, social work, economics, psychotherapy, geography, biomedical science, and much else.

These publications have been widely spread across diverse journals and publishers. Now there is a home for all types of Beatles-related research.

Having decided to submit a paper to the journal, I then needed to choose a suitable research topic. (This is doing things backwards, really. Normally one does the research and then worries about which journal to try to publish it in.)

The research topic needed to be something original, interesting, and feasible. I decided to do a quantitative analysis of their core tracks – the 217 studio-recorded songs they released through EMI between 1962 and 1970. I realised that although there is a massive amount of information available about these tracks, nobody had ever pulled it together in a quantitative way to see what can be learned that we didn’t already know.

I created a database for the 217 tracks and identified about 100 variables that could be quantified for each track. The variables included things like the duration of the song, who wrote it, who performed on it, what instrument(s) they played, who sang lead and backing vocals, the song structure, the lyrical themes covered, how long it took to record the track, the time lag between recording and commercial release, and the number of separate tracks on the tape recorder used to capture the song in the studio. There are over 20,000 distinct pieces of data in the database. Quite a lot of the information was already in my head, but I had to double-check it all and chase down details I didn’t already know. As you can imagine, it took ages, but what fun!

Having pulled the database together, I used it to explore how the songs they released evolved over time from 1962 to 1970. It’s obvious to anyone with a passing knowledge of their music that the degree and speed of change in their music were scarcely believable, but I was able to be very specific and precise about the changes that occurred. Some changes are easy to recognise (e.g., the move away from songs about romance and relationships after 1965) but others are not at all obvious if you don’t study the data.

After I submitted the paper, the peer-review process proceeded smoothly and it was accepted for publication after one round of revisions.

You can read the whole paper here. You probably won’t be able to stop yourself, but just in case you need some encouragement, here are a couple of the results to entice you.

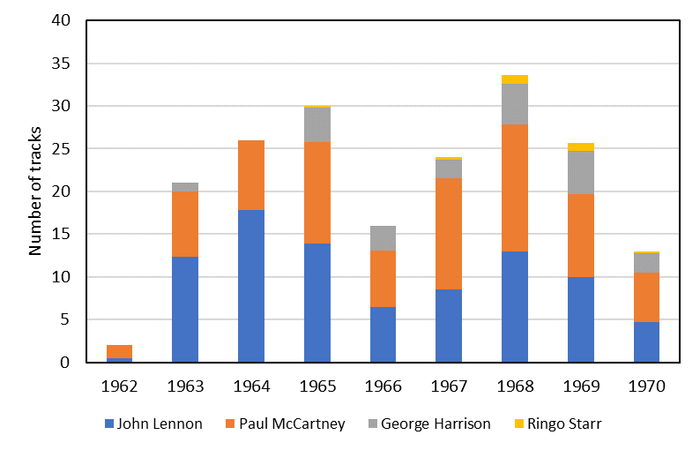

Figure 1 shows how many of the Beatles’ released songs were written by each of the four Beatles. Most were officially credited to Lennon and McCartney jointly, but the results in this graph are based on information about who actually wrote how much of each song. Overall, based on Dowlding’s (1989) allocation of song-writing effort between each of them, and summing each fractional contribution, Lennon was responsible for 87 songs, McCartney for 79. This result might be seen by some as surprising as McCartney has a reputation for keenness and diligence while Lennon had a reputation for sleeping. John had a clear lead in the early years while Paul had a slight lead in the later years.

After a slow start, George Harrison became a consistent contributor of songs from 1965 on, with 22 songs in total. The only two Beatles songs for which Starr received more than token song-writing credit were released in 1968 and 1969.

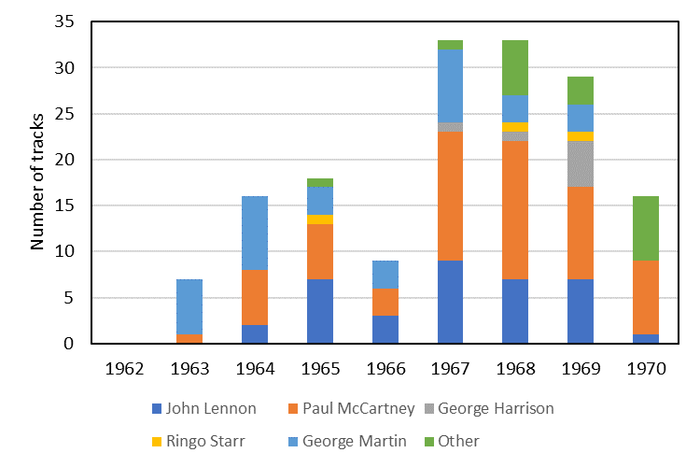

The Beatles each played multiple instruments. None of them was a specialist at keyboard instruments, but they all played keyboards on at least some songs. Figure 2 shows the number of tracks on which keyboards were played by each of the Beatles, by their producer George Martin, or by someone else outside the group.

Use of keyboards in their recordings increased dramatically after the Beatles ceased playing live concerts in 1966, with McCartney being the main player, but with Lennon, Harrison and even Starr making contributions. George Martin was an important contributor on keyboards in 1963, 1964 and 1967 and an occasional one in other years. Of the outsiders who contributed keyboards, the most obvious was Billy Preston, who played on many of the tracks on the Let It Be album (1970) and also helped a bit on Abbey Road (1969).

If you found those graphs at all interesting, you’ll love the paper. Check it out here.

Further reading

Dowlding, William J. (1989) Beatlesongs (New York: Simon and Schuster).

Pannell, D.J. (2023). Quantitative analysis of the evolution of The Beatles’ releases for EMI, 1962 – 1970, The Journal of Beatles Studies, Spring/Autumn, https://doi.org/10.3828/jbs.2023.5

Hello David

I so loved this article, passion for ones work is a gift and the passion you have for the Beatles is undoubtable – well done you on finding a way of combining your research mind with your healthy Beatles obsession.

I hope you’re well.

Gillian

Thanks Gillian.

The older I get, the more important it becomes to do something whacky! Full marks to you, David. I predict you’ll live to 100. I trust you know of these beautiful arrangements of Beatles tunes for classic guitar:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqnO4O0ZxiQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C95R0tsX5rw

Dear David,

I can hear your excitement ringing through your blog! Congratulations, I am very excited for you!

Funnily enough, it was only the other day that the significant other (bit of a music nut) and I were discussing which of the Beatle members wrote the majority of the songs. I can’t wait to share your insights!

Love how you have combined your passion of music and numbers.

Louise

I don’t know how many papers I continue to read over time but thank you for sharing this one. I didn’t know I had a much more subdued fascination with the Beatles until reading your analysis.

Lovely to see good research rewarded. Me, I just wanna be a Paperback Writer

Sir or madam

Will you read my book

It took me years to write

Will you take a look

David, Congratulations! Here Comes the Sun, and with it, a new day full of possibilities. Remember, All You Need Is Love and a little bit of Help! from your friends to make it through. So, Let It Be and embrace the journey. After all, In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make. Keep shining!

Hi Dave

Fantastic. I remember your Discussion 293 about your trip around Liverpool etc. Great to see you can now contribute, not just observe. As another oldy, I loved John Cotter’s comment, above, re doing something whacky.

All the best

Alistar

What motivated the author to submit a paper to the Journal of Beatles Studies, and what unique approach did they take in choosing a research topic?

Teknik Informatika

Motivation = love of The Beatles and the challenge of getting into the journal.

Unique approach: that’s explained in the Pannell Discussion.

David — this is amazing! Is your database anywhere for download? I’m interested in doing some of my own visualizations about the Beatles’ output.

best

Gar

Thanks Gar. Glad you like it. I’ll email the database to you.