381. Why are fertiliser prices currently so high?

Since late 2021, fertiliser prices have been affected by a combination of factors, pushing them to record high levels. It is probably the issue that has exercised farmers’ minds the most over this time. What factors have caused this, and what are the prospects for 2023?

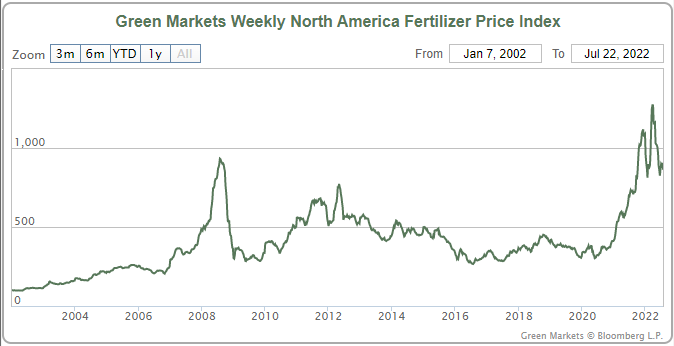

The figure below shows how high fertiliser prices have been lately compared with the past 20 years.

In PD360 I discussed farmers’ potential responses to high fertiliser prices. Recently I gave a talk to farmers at Hyden in the Western Australian wheatbelt, including an outline of the reasons prices are so high now.

The initial trigger was a rise in energy prices in 2021. Manufacturing fertiliser is energy-intensive, especially for nitrogen fertiliser, so rises in energy costs make a big difference to the cost of production.

A consequence was that some fertiliser manufacturing plants suspended production or even shut down. This was particularly the case in Europe (where fertiliser production is relatively expensive) and China (which is easily the world’s largest fertiliser producer).

The next event was that, in response to lower production, China took steps to make it more difficult for fertiliser to be exported.

In some ways this is an understandable response. It is not all that long ago that most people in China were hungry most of the time, so food security looms large in the minds of the Chinese Government.

On the other hand, if there is a country in the world that could get by with less fertiliser, it is China. Their farmers apply massively excessive rates of fertiliser, supported by government subsidies that make fertiliser cheap to them. The application rates used are way beyond the level that would make economic sense, and in many cases they could be cut substantially without any sacrifice in yield.

Their excessive fertiliser rates are very costly financially but also environmentally. They cause China to have some of the worst water pollution problems in the world.

Their excessive fertiliser rates are very costly financially but also environmentally. They cause China to have some of the worst water pollution problems in the world.

Be that as it may, China acted to prioritise fertiliser supply to its own farmers, reducing supply to international markets and thereby pushing up prices.

Also contributing to some degree were disruptions to supply chains caused by COVID-19. These weren’t the main factor but they added to the pressures.

By the end of 2021, farmers were already grappling with what to do in response to very high fertiliser prices. Then came Russia’s attempted invasion of Ukraine, which compounded matters in various ways.

Firstly, it pushed up energy prices even further. Europe’s efforts to minimise its reliance on Russian energy meant that they started competing for other energy sources.

At the same time, Russia imposed quotas on exports of fertilisers and prioritised supplying them to countries that it viewed as not unfriendly. Russia is in the world’s top five producers for all three of the main fertiliser types, nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, so them cutting exports can make a big difference to prices.

Then Europe imposed restrictions on exports of potassium fertilisers from Russia and Belarus. My guess is that this is targeted at hurting Belarus, Russia’s only ally in the war. It so happens that Belarus has a lot of potassium in the ground and it is the world’s second or third largest supplier (about equal with Russia). Or at least it was until Europe made it much more difficult for them. For example, Lithuania has halted use of its rail network to transport Belarussian potash to port.

The next big factor is subsidies on fertilisers in the main fertiliser-using countries. I’ve already mentioned the subsidies in China, the world’s largest fertiliser user, which was providing about $300 per tonne of fertiliser. I don’t know exactly what they’ve done with that currently, but by keeping domestic fertiliser supply high, the implied subsidy must be even greater.

Even more extreme is India, the world’s second largest fertiliser user, which subsidises its farmers’ fertiliser costs by about 90%.

Thus, farmers in the two largest fertiliser-using countries have no need or incentive to cut their fertiliser usage. Since there is less fertiliser available in the world, it means that the required cuts in usage have to be concentrated on farmers in the rest of the world, resulting in intense competition for the available fertiliser and an even more extreme escalation of prices than would be the case without the subsidies.

Finally, the prices of grain have been high as well, increasing farmers’ motivation to apply fertilisers despite their high costs, flowing through to further upward pressure on fertiliser prices.

What are the prospects for lower fertiliser prices in 2023? I’ve said before that the best cure for high prices is high prices. They prompt suppliers to increase output and purchasers to cut demand. We’ve seen the latter, and we are now seeing the former.

For example, there are five new plants for manufacture of nitrogen fertiliser under construction in India, with the ambitious aim of being self sufficient in nitrogen within 18 months. Major suppliers of other fertilisers are also trying their hardest to ramp up supply, notable Morocco for phosphorus and Canada for potassium.

The question is whether the fruits of these efforts will be large enough and soon enough to lower prices for 2023. A lot depends on Chinese policy and the Russian war, of course, so anything could happen, but the general sentiment amongst industry players and watchers is not optimistic.

In May, CF Industries (the world’s largest nitrogen fertiliser company) predicted the product will remain expensive for two more years. China’s export restrictions were initially scheduled to end about now, but the Bank of America recently said that China seems set to extend export restrictions on fertilisers through to mid-2023. Potassium prices are particularly dependent on supply from Russia and Belarus, so if the war, sanctions and export quotas continue, prices will stay high.

So, unfortunately, it seems that farmers should be prepared for at least another year of high fertiliser prices.

Further reading

Pannell, D.J. (2021). Potential farmer responses to extreme prices for nitrogen fertiliser, Pannell Discussions, 360.

Dave: Thanks for an interesting post. With India pushing so hard to increase domestic production, does that also imply they will be in the market to import for substantially more natural gas in the near future, with Russia the most likely potential supplier? .. do all roads in this market lead back to authoritarian regimes…

Yes, logically it does seem to point in that direction. Russia does seem to be cultivating its friendship with India. It’s one of the places Russia still sells its fertiliser to.

I’m a farmer in Ireland; I sell my milk forward (bad idea sometimes) and buy my fertiliser forward sometimes. Massively reduced and focussed on fertiliser/value of slurry- people are buying shite (literally) from me. But how do I reduce my exposure to prices of E1500 a ton?