397. Responding to journal reviews

Research papers that are submitted to journals for publication are sent to independent reviewers, who have the task of assessing whether the work should be published and suggesting ways that the paper could be improved. For researchers, responding to the reviewers’ comments can be challenging. How should you approach it?

There are three aspects of “responding” to reviewers: (a) responding emotionally to the comments you receive, (b) preparing a document that describes how you have responded to each of the reviewers’ comments, and (c) making changes to the paper.

Responding emotionally

Be positive.

If the editor’s decision is to reject your paper, you need to consider whether any changes are needed before sending it to another journal. (I like John Quiggin’s comment below: “If you’ve been rejected, ignore all the comments except those that are actually helpful.”) Just soak it up and get on with it. Don’t sit on the paper for ages while you recover from the rejection – keep it moving.

If the editor’s decision is to ask you to revise and resubmit your paper, you should be happy, even if the reviews are annoying. The chances of a revise-and-resubmit paper eventually getting accepted are pretty good.

Even if you get a revise-and-resubmit decision, a common experience is that, on first reading, the reviewers’ comments seem more negative and more difficult to address than they really are. You can find yourself responding emotionally to the criticisms that the reviewers make of your work, especially if you don’t agree with them. This is understandable, but not helpful. It might discourage you from revising the paper, but you should just get on with it. And when you do get on with it, you could well find that the changes you end up making to the paper are less extensive and less time-consuming than you first expect they will need to be.

It can be helpful to have an initial read of the reviews, then put them aside for a few days while you think about the comments (and calm down) and then come back and read them carefully again.

The response document

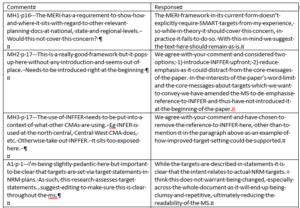

Before editing the paper or going and doing new statistical analysis or model runs, the first thing I suggest you should do is to create a table with two columns in your word processor and copy all of the reviewers’ comments into the left column. The heading for the left column is “Review comment” and the for the right column it is “Response”.

Each comment that needs a response goes into its own row. If a paragraph of the review contains multiple items that need a response, put each of them in a separate row.

Each comment that needs a response goes into its own row. If a paragraph of the review contains multiple items that need a response, put each of them in a separate row.

Create a separate table for each reviewer, label which reviewer the table is for, and start each table on a new page.

This document with the tables in it eventually becomes the response document that you send back to the journal. It also provides you with a todo list as you revise the paper.

Before each table, insert a sentence or two thanking the reviewer for their helpful comments and giving a brief outline of how you’ve changed the paper. For example, “We have attempted to fix all of the issues you raised.” Or maybe, “We carefully considered all of your comments and found them helpful in improving the paper.” The latter version could work if you have not accepted all of the reviewer’s comments.

Don’t try to avoid a reviewer’s comment by leaving it out of the response document. It might be tempting, but you will just annoy the reviewer when they look at your paper again, and annoying a reviewer is not a good idea.

It may be helpful to note down in the table your initial ideas of how you will respond to the more substantial comments and share them with your co-authors to get their input.

Changing the paper and filling out the response document

Generally, it is best to start by viewing every review comment as an opportunity to improve the paper. Even the dumb ones could be a signal that you haven’t explained things clearly enough.

Of course, some review comments really are not helpful, and it is acceptable to choose to reject them, but you should consider whether there is some change to the wording that will make it less likely for a reader of the paper to fall into the same mistake as the reviewer has done.

Turn on track changes before you start editing the paper. Save it to a new file name ending in “tracked”.

Turn on track changes before you start editing the paper. Save it to a new file name ending in “tracked”.

I like to start by fixing up the easy things first, to create a feeling that I am making progress. As you make each change, describe in the response document what you have done. As the right column of the response table gets filled in, you can monitor your progress and easily see what is left to do.

If the change is a simple one that fully meets the reviewer’s request, your response in the response document can be very simple – e.g., “Done” or “Sentence edited as requested” or something like that.

If it is not so simple, you need to convince the reviewer and the editor that you have taken it seriously and made changes to the paper that really address the comment. Of course, they can see that when they re-read the paper, but you should aim to make things as easy as possible for the reviewer and the editor. You want them to be on your side. To that end, it can be helpful to first describe what you have done and then provide a quote of the relevant text that you have edited or added.

If you feel you must reject a reviewer’s comment, in the response document you explain why. Be very polite, even if you think it’s a silly comment. You could say that you understand the comment and you’ve really tried to find a way to accommodate it in the paper, but after careful consideration, the authors would prefer not to do it for reason X.

Sometimes you cannot understand what the reviewer is trying to say. If that’s the case, make it seem like you tried hard to work it out. We think you might mean X or Y, but we aren’t sure. X seems more likely, and we’ve made certain changes (if you have). Or, we cannot work out the intent of the comment, so we’ve made no changes to the paper at this point, but we are happy to reconsider the comment if it is clarified.

If you are unlucky, you’ll find that different reviewers of your paper have comments that contradict each other. The temptation is to ask the editor which version to accept, but remember that the editor is super busy and doesn’t have time to respond to this sort of question. It’s up to you to weigh up the comments and make a choice which one you will accept. In the response document, for the comment you reject, you can explain that you received contradictory comments from different reviewers and had to make a choice, and say why you made the choice you did.

Everyone in the authorship team should contribute to the revision process. The lead author probably does the initial work, but then there is a process of sharing the files back and forth between the authors until everyone is satisfied.

Do a careful final check of the revised paper and the response document. Then, save the edited paper file, switch off track changes, accept all the tracked changes and save it to a new file name ending in “clean”. Submit both files (tracked and clean) to the journal, along with the response document.

Now try to forget about the paper until the editor’s next decision.

Further reading

Pannell, D.J. (2023). Resources for PhD students: information your supervisors may not tell you, Pannell Discussions 391, here.

Thank you David, for putting this all down so clearly. It is similar to what I do, although I have one additional suggestion; when I write out the to-do list for a paper with co-authors, I indicate who should do what. Some co-authors are better at addressing certain issues than others, wrote that part of the paper, etc. Laura

Excellent advice, David. My first atrocious review from a professional editor hurt terribly but it taught me a great deal and is part of the induction process to the club of journal contributors. Reviews should be considered like bread and butter and not taken personally. Learning to deal with professional criticism is a fine thing and advances your own objective thinking.

Good advice. I would add one point.

If you’ve been rejected, ignore all the comments except those that are actually helpful. With luck, the referees will never see your paper again. With a Revise and Resubmit, implement all the suggested changes except those that are positively harmful.

Good stuff Dave – I chuckled when I read “thank the reviewer for their helpful comments” – which is a nice way of ignoring their “unhelpful comments”.