266 – Supply and demand: The wool crisis

The wool crisis of 1990-91 was a spectacular case of economic mismanagement, where an industry inflicted massive costs on itself (and others) through acts of obvious and determined stupidity. Industry leaders convinced Australian wool producers to endorse a strategy that was completely devoid of economic sense. The aim was to make producers rich, but the result was that they lost billions of dollars.

What they did was establish a reserve price, below which they would not allow wool to be sold. That needn’t have been disastrous, except that they set the reserve price optimistically during a period of booming demand, and then refused to lower the price when demand cooled. Farmers kept receiving the artificially high price and so  produced huge volumes of wool – much more than they would have done at the real market price. At the same time, wool buyers responded to the high price by reducing their purchases of wool and switching to other textiles. The predictable result was a huge stockpile of unsold wool.

produced huge volumes of wool – much more than they would have done at the real market price. At the same time, wool buyers responded to the high price by reducing their purchases of wool and switching to other textiles. The predictable result was a huge stockpile of unsold wool.

The industry borrowed billions of dollars to pay itself inflated prices for its own wool, put it in sheds and pay storage and interest costs, hoping that the price would rise again, but actually creating ever-increasing pressure for it to fall. It really was as ridiculous as that sounds. It’s hard to imagine how anybody involved could not see the folly in this, but somehow wool-industry leaders convinced themselves and most wool growers that it was a good strategy.

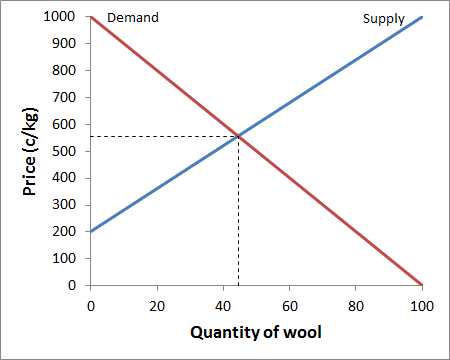

Figures 1, 2 and 3 illustrate what was happening, in a simple supply and demand model. Figure 1 shows what the price and quantity would have been in a free market: a price of 555 c/kg, resulting in a balance between supply and demand, at 44 units. (These are not the real numbers – they are just for illustration).

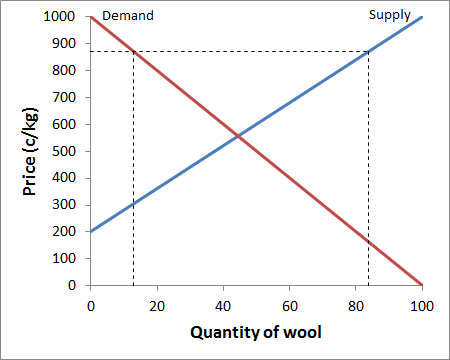

Figure 2 shows what happened when the Australian Wool Corporation (AWC) set a high reserve price (of 870 c/kg), and passed that price on to farmers. Because of the artificially high price, demand for wool was reduced (to 13 units in this illustration) while production of wool was increased (to 84 units). The wool that wasn’t bought (71 units – the difference between production and sales) was acquired by the AWC and stored indefinitely.

Just as in Figure 2, the AWC found itself having to acquire most of the wool being offered to the market. By the end of the scheme, the amount of wool being stored reached extraordinary levels (4.8 million bales, approaching a billion kilograms), and it was incurring around $3 million per day (over $1 billion per year) in costs of storage and interest.

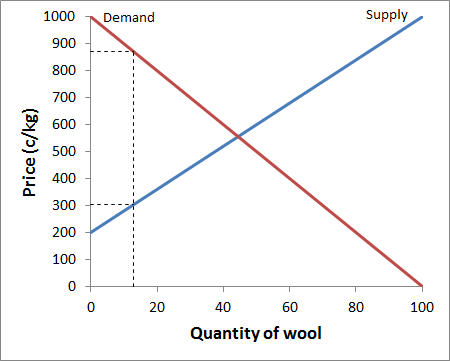

The sensible way to get rid of over-production would have been to abandon the reserve-price scheme, but instead the AWC decided to tax the price received by wool producers. Presumably, the aim was to bring the amount of production down to about the volume of wool being purchased. Figure 3 illustrates this outcome. In this figure, wool buyers are still being charged 870c, so they are still only purchasing 13 units. Wool producers are being taxed 566c, so the price they receive is only 304c, resulting in production of 13 units (matching demand).

If the original reserve price system was stupid, this system of taxing producers was stupid squared. For it to eliminate surplus production, wool producers would have had to receive a lower price, and produce less wool, than in a free market. And this was a system that was intended to benefit wool producers!

Throughout the drawn-out crisis, proponents of the scheme argued that the shortfall in demand could be overcome through market promotion, and a big chunk of the wool tax was spent on this. A tenacious faith in this idea was partly what drove them to stick with the scheme long after it was clearly a disaster. If the experience proved anything, it’s that this faith was unjustified.

Another factor driving them to stick doggedly with the scheme was an apparent unwillingness of the decision makers to admit that they had made mistakes. The delays in shutting it down greatly escalated the costs.

Eventually (much later than it should have) the Australian Government exercised its power to force the AWC to lower the price and later shut down the scheme. The AWC fought it all the way.

Wool producers, processors, traders and Australian taxpayers all lost money in this scheme. Charles Massy in his excellent book “Breaking the Sheep’s Back” estimates that the total cost was at least $12 billion in 2011 terms (and probably much more), making it “the biggest corporate disaster in Australian history in terms of losses generated by a single corporate or statutory business entity” (Massy, 2011, p.382).

At the time of the crisis, I was living out in the wheat-sheep belt of Western Australia, so I got to hear much of the debate at the grass-roots level. Some farmers could see that the industry was making a massive mistake, but most were following the lead set by industry leaders and blaming the scheme’s problems on everybody else: politicians, economists, wool customers.

It would be hard to imagine a more incompetent and irresponsible set of decisions than those of the AWC board and management throughout this episode. As a result they caused untold human misery. We can count the billions of dollars lost, but we don’t have statistics for the depression, the suicides, the fractured families or the agony caused to farmers by having to shoot and bury thousands of worthless sheep. I don’t think those responsible for this misery have ever been adequately held to account.

A really basic understanding of economics would have avoided all of this. Not only did the industry leaders lack this understanding, but, as Massy reveals, they actively resisted and rejected advice from competent economists when they received it, including economists who worked for them.

An online review of Massy’s book sums up one of the key lessons very well: “Those who defy the markets will eventually lose. They may lose slowly, or lose in a spectacular collapse, but they will lose.”

Further reading

Bardley, P. (1994). The collapse of the Australian Wool Reserve Price Scheme, The Economic Journal 104(426), 1087-1105. IDEAS page

Massy, C. (2011). Breaking the Sheep’s Back, University of Queensland Press. Here

Richardson, B. (2002). The politics and economics of wool marketing, 1950–2000, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 45(1), 95-115. Journal page here

Is today’s situation with rice in Thailand the same, if not worse?

Hi Neil. Current Thai rice policy does have some key things in common with Australian wool policy in the 1980s-90s. The Thai government has set a price for farmers that is about double the market price. As a result, production has boomed. A big stockpile of unsold rice has built up. And yes, the costs look like they are roughly similar in magnitude, and perhaps even bigger.

There are some differences too. In Thailand it was a government decision (for electoral advantage) rather than a decision of the industry. It is mainly the government that is bearing the cost (billions of dollars per year), rather than the farmers. It doesn’t pose a threat to the long-term prospects of the Thai rice industry. Thai rice is a much smaller percentage of world production, so the scheme is having a smaller impact on traders, processors and other producers around the world. Once they abandon the scheme (as they will have to sooner or later), they should be able to return to more-or-less where they would have been without the scheme, whereas for wool there had been irreversible substitution away to other fibres. The Thai situation is made worse by corrupt officials, and by people bringing in rice from neighbouring countries to sell at the inflated prices.

http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21583281-increasingly-unpopular-government-sticks-its-worst-and-most-costly-policy-rice-mountain

I agree that the price set by the Thai government was way above the equilibrium price and instead of helping the farmers corruption resulted in the whole rice scheme failing. I however do support government intervention when it comes to farmers because the majority of farmers cannot compete world the world prices of agricultural products.

I think it is easy to justify government support for people on welfare grounds, such as benefits for people on low incomes or unemployed people. However, I don’t think it makes sense to provide benefits to people just because of the type of business they run. For one thing, why should that business be more worthy of government support than another type of business that is struggling just as much? Secondly, history shows that the great majority of payments under agricultural support schemes go to large wealthy farmers who don’t need the money. On average, these schemes take money from less wealthy people and give it to more wealthy people.

I liked the final part of your comment and you are right, the attention should not be to a single item, there many producers who struggle to get their crops, however, they are not even looked at

In all, policymakers should always allow the forces of demand and supply to set the prices of agricultural products. Government task should creating enabling environment for farmers in order to attract younger generation.

Hi David, this resonates with me because my firm is involved in rice processing here in Nigeria. I know a lot of producers in Nigeria imports rice from Thailand via port and smuggling.

But despite the inflow of rice from Thailand, the price of rice is yet to crash as demand keeps increasing and the quality of homegrown rice is struggling to match that of the ones from your country.

Legend has it, that the reason why it is cheaper to smuggle rice in from Thailand is because those rice are the stored ones which you are talking about here.

The situation that you describe has been seen in Mali it 8 years ago. With the higher prices of the products especially rice in 2008 which caused strikes in diverse Sahel countries including Mali, the Government has subsidizing agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizers which contributed to boost rice production. At the same time, the Government has reduced the taxes of rice and traders enjoy to export thousands of tons coming competition with local rice. Malian consumers who have a low very purchasing power are turned to the imported rice who cost 2 times cheaper than local rice. Rice farmers could not repay inputs subsidized price credit have sell off their production and most especially small producers have quit the countryside for the city looking for other opportunities.

David, I have to admit that I was only a kid when I was dragged along to a wool scheme rally at the height of the issue. But I still remember that the issue was very much irrational and emotive. A lot of farmers were all about getting paid to produce, it was someone else’s problem to sell the stuff.

To some extent there is a lot of that in all the pooled ag commodities. You only have to look at the way people reacted to the wheat board changes. Many regard themselves only as growers and don’t care about the end market, demand or, surprisingly, the price. The last point caught me off guard, but it was front page of the FarmWeekly (the season after the peak in wheat prices), with a farmer standing in a crop in spring saying he needed $300/t to break even, that made me realise how unresponsive farmers are to change, especially in their produce markets.

Thus, they loved the floor price, it made everything easy.

So, market economy should manage the price, then it’s good if a grower could predict the price then decide which to transplant? 😀

David.

The most significant damage to the wool industry was from the existence of the stockpile even after the scheme was abandoned. In effect it meant that there was an unlimited supply of wool overhanging the market, and of course the supply/ demand relationship is really a psychological one. It is a perception.

At that time I suggested that the entire stockpile should be destroyed…..dumped and buried in the Kalgoorlie super pit. While that was the equivalent of tearing up billions of dollars, producers would still have been better off overa period of years. One of the replies I got was, “I have too much money invested in the stockpile.”

That was one of the options on the table. A lot of analysis was done to identify the best strategy overall. From memory, I don’t think destroying it came out best.

What happened to ask that wool? I can imagine so many businesses benefiting from that huge stockpile, and the blight of the AWC, and make millions by producing and selling innovative and probably not so cheap wool based products.

There ought to have been done savvy business man or other getting rich during this crisis?

In Farsi, we’d say “catch fish from murky waters”.

Situation is even more worst in my country Pakistan. Now the potato harvesting season is going on here in Pakistan and Govt do not set any price for potato to benefit the formers and today’s price for potato in local market is US $ 10/100 kg.

Thanks for offering this course on line, who said there is no free lunch.

Kindly shed some light on minimum wage in the context of food security. Thanks

Dear David Pannell

What would you say about the prices of cotton in Pakistan?

Where India and china is giving subsidy to their farmers in cotton production (violating the WTO rules) and Pakistan dont give any subsidy. And poor farmers are suffering.

I don’t know what Pakistan is doing with cotton prices. In general, my starting point is that any assistance provided to farmers should not be built into prices. If the government wants to give assistance, it should be by some other way, such as by a payment that isn’t built into prices.

In Vietnam, the government set the price rice is too low. Then the middlemen (collectors) buy rice from farmers to low then middlemen and exporters got most of benefit, farmers (producers) get too little benefit from the rice value chain and have very low power to make decision on price

In some situations large companies (or governments) in the supply chain have market power and can reduce prices to farmers below a competitive level. There can be a role for government intervention in this case. I would be regulating the supply chain, rather than subsidising farmers.

Dear Dave,

Thanks for the educative piece on the importance of Demand and Supply.

In my country Nigeria, the impact of Nigerian government is not felt much by the farmers; hence farmers are on their own. On many occasions, there are gluts in the markets and farmers are losers because they will have to sell at ridiculous prices which will lead to loss.

It is my prayer that government in Nigeria will have strong policy and financial assistance for farmers so that many people will develop interest in farming which is the mainstay of the economy.

Best regards,

M.O. Falola

I don’t know about Nigerian agricultural policy, but it is true that historically many developing countries have had policies in place that favoured urban dwellers and penalised farmers. This is really not a good idea, especially given the large numbers of farmers.

Another angle to this Moses,

Look at rice production in Nigeria; after FG invested through CBN, BOA and other tools, then they opened the border and imported rice flowed through, leaving rice processors in dire state.

Policies has to be progressive and not the “putting cart before the horse” that the government is doing. They can’t shut an alternative source of supply when they have not ensured that the nation is self-sustaining.

Hi David

You said that government assistance to farmers should not be built into prices. As you are aware that agricultural crop cultivation is not a profitable activity in developing countries. Given that do you advocate producer subsidies are as good policy tools to assist farmers in developing countries? I know that Sri Lankan government use the fertiliser subsidy to assist farmers.

Thank you

Rupe

Building assistance into input prices is usually not quite as bad as building it into output prices, but it is still not a good idea. Subsidising inputs leads to over-use of those inputs, and can create problems such as water pollution or simply waste. If assistance is to be provided, it should preferably be provided as a direct payment to farmers that doesn’t affect input costs or output prices. An exception could be where an input creates external benefits.

I think the best assistance is educational subsidies for farmers’ children (and even farmers themselves) so they don’t keep making these mistakes and supporting policies which are against their interest.

Hi about the falling of the wool industry is the major focus by the economy was to see that it increases the demand of wool in form of raw materials to factories thanks

In India still fertilizer subsidy is not streamlined. But government has started giving direct subsidy /cost to the LPG consumers. Instead of giving subsidized LPG the subsidy amount is directly credited into consumers bank account.

Putting a subsidy straight into a bank account sounds better than building it into the price. It avoids distorting demand for the product or input.

This is certainly an eye opener into economy of the Wool Industry for me. I never knew this and am pretty sure there are other industries facing this dire situation with leaders who only wants to make money.

Hello David

I regret to say that the same manipulation is being done by the Pakistan Government for the production of wheat.

Firstly they declared that the production is going to be less and market price will be high in this year.Mostly people changed their cropping pattern and focus on the major wheat crop as well. But in vain farmers have to survive at he last.

Govt has declined the prices upto 40 %.

Farmers are not subsidize with the conditions relating to issue and also not legislation for the cropping pattern so that analysis can e done and further evaluation can be possible. What is your suggestion if govt does not co-operate and we have to survive it on our self

Regards

Faisal

Hi David,

Like your article on 1990s Wool crisis remember it well – been in mkts 25yrs & as per current Chinese Stockmkt crash no one seems to learn about damage done from trying to fix prices – certainly makes it interesting – I call it the “gold fish theory” mkt can’t remember what happened 24hrs ago let alone 20yrs.

Cheer Ross McInnes

What will be if Producers and Sellers will know how make supply curve, demand curve and to find our Market equilibrium price and Market quantity.

A great article, knowing this, agroindustry in many countries would act more logically in markets; the problem with taxes and protectionism causes more costs in markets, then countries need to set up different ways to stablish trade barriers for imports and protect local farmers.

Hi David, thanks for offering this course. I am beginning to be part of the international coffee trade and currently Climate Change, industry consolidations and producer poverty are pushing new conversations into alternative price mechanisms that can reflect changing cost of production and keep famers motivated to stay in coffee. Are there lessons from other industries and/or further reading you could recommend to be personally better prepared to understand this through a wider agricultural context? Thank you

In my view, one of the key lessons from experiences like this is that you should not be looking for alternative price mechanisms to keep any farmers in any particular product. The risks in trying to do so are too large. A better strategy would probably be to invest in research and development to create production systems that are more efficient or more productive.

I support David Pannell because strategy is the key in any organization which provides proper directions and success and therefore would also reckon that better strategy would also be to invest in research and development. This will enhance and create productive systems which are efficient and more productive.

Dear David,

The same situation except that there was no reserve price for silk in southern states(provinces) in India . The price for silk cocoons was very high during 2011 this promoted the farmers to take up Sericulture in non conventional areas, but now due to increase in supply the Government has taken measures like reducing the import duty of silk. So now since import duty is less textile industries started buying silk from Chinese, this made the the producer get less price hence growers uprooted the plants and this policy made a balance in demand and supply. This is just one side of coin.

But the real problem is majority farmers here own land only for subsistence living so what to do with such consequences?

Dear David,

The price management of staple crops in Nigeria is yet to to standardised, however, the improved value chain management of some few staple products e.g rice and cassava has helped stabilize the prices. Presently the Rice anchour project in Nigeria is producing more rice for sale (a good business synergy between the small and medium contract farmers , Big Rice Millers and corporate Organisations). Prices are still high yet stable.

I believe in no distance future in Nigeria, the market equilibrium for most staple food will be at relatively lower price.

Hello David,

This course has really enlightened me in the economic and social consequencies of government and other board policies which may be overlooked at the time of planning and implementation. Thank you very much. In Ghana, it is only cocoa that the government through a board regulates the prices. For some time now, there hasn’t be any challenge probably because about 75 percent of raw cocoa beans is exported. I am also informed that the selling price of cocoa by the board is hedged on the international market. Coordination along the cocoa value chain cannot also be underestimated. I think they have achieved a lot.

David,

I was a teenager being raised on a sheep farm and lived through this crisis.

This article certainly brought back memories. Shooting sheep and throwing them in a pit is an awful memory that has never left me.

I recall in our area that all the blame was with the Japanese. What was the rationale behind this?

Yes, I never witnessed it, but I certainly talked to farmers who were deeply affected by having to shoot their sheep.

There were wool processors in Japan. Blaming them was completely nuts. The problem was entirely created by the Australian industry, and the Japanese processors lost heaps of money – they were victims.

I am following the discussion.

This is excellent

Excellent example. Thanks!!

I really love this discussion!

A good case study.

Thanks!

interesting case study and we have learnt more about the development in Australia and Thailand

A big lesson, not politicized and ended in a great loss

Hi Mr. Pannell,

So, If suppose the reserve price of the wool was dynamic and was a factor of the then market supply and demand ratio, But still securing the livelihoods of the farmers, in terms that they manage to earn the part what they invested while taking care of the sheep and the processing charges etc. Would it have been the correct implementation of the scheme ?

What I dont understand is, generally farmers are promised minimum prices to save them from the pain of facing the extreme low market prices, which does not even cover their investments put into the production. If we wish to save the farmers from facing unjustified market prices during bulk production, we are bound to have a minimum price, but then that would always drive the farmers to produce more than required. Do you think predictive analysis of production could be a solution ? I mean, if the government/other agency could announce the amount of required produce in advance and the farmers grow following that, ( but that again would be very ideal place to live in)

In this case, it was farmers themselves who effectively agreed not to sell their wool unless the price was above a threshold price. This is a really stupid strategy for a whole industry to adopt. It led to all the problems described in my article.

In some countries, minimum prices are guaranteed by governments. The system used in Thailand to increase the price of rice is a good example. This is also stupid, and has wasted billions of dollars. It inevitably fails at some point.

If the purpose of the policy is to help farmers, the best approach is to help farmers as directly as possible. Give them money as a direct payment, independent of how much they produce, rather than building it into prices. That results in a much more targeted and effective approach. If you build assistance into prices, the farmers who get the most assistance are the ones who need it least.

“Give them money as a direct payment, independent of how much they produce” completely agree with first but would like to understand second line where you mentioned ‘independent of how much they produce’. for e.g if we have to pass-on direct benefit to 4 farmers A,B,C & D who are cultivating wheat on 2,3,4 & 5 hectare of land respectively, what should be the criteria to benefit them with direct payment?

It depends on what the objective of the program is. If the aim is to help the most-needy farmers, you might set up a scheme that gives more to farmers with less wealth. Or if the aim is to help all farmers equally, you could give the same payment to every farmer. Or if the aim is to help all small businesses (including small farmers) you could give the same payment to all businesses with a turnover less than a certain amount. All of these options have risks attached, though. People would make efforts to restructure or re-organise their affairs so that they qualified for the payments. e.g. split a farm in two so that you have two smaller farms (e.g. owned by husband and wife), so that you qualified for two lots of payments. This effort would be a waste of time in terms of producing more food or wealth. It is very difficult to anticipate and think through all the perverse incentives that this sort of scheme creates. One thing that’s clear is that the dumbest thing you can do is build the assistance into output prices, which mainly helps the people who least need the help.

Hello David

In your discussion you mentioned how seasonality can affect the supply/demand nexus. What about quality as another factor? If the quality does not achieve benchmarks, then presumably it throws the market equilibrium price out of kilter?

It doesn’t throw the market equilibrium price out of kilter. There are different prices for different quality wools. There is some degree of substitution between the different quality wools, but also sort-of different markets for them.

Hi All,

I am Johnson and it is really for joining this course.

Hello David,

I really thank you for knowing the importance of demand and supply . I also want to know how to impact the gorvement policy on market price. In Myanmar, most farmers get less benefit than the traders. I think the traders can defy the rice market in Myanmar.

But, they still are succeeful nowaday.

Wow, over 12 billion $ lost! I always thought that cooperations are very well informed and very smart in everything that do.L

In Myanmar, the real price of rice are not the same with the rice association’s prices. Although

rice can export legally in Myanmar , illegal for other countries. Most of myanmar crops and sesonal vegatables face like rice. What should we do?

Thanks for offering this course on line, I really appreciated.

Thank you for letting us know about these cases, they are very important for us to understand what you are explaining about demand and supply.

Historically the price control always bring economic disaster. Especially when the government gets inside in decisions markets (Rome, USSR, Cuba, Venezuela…)

Reading these comments has definitely cemented my understanding of demand and supply and its time for cooperates and governments to not only involve economists but to listen and abide to their assessments.

It’s a useful case study. This shows that decisions are supposed to be made according to the prevailing economic conditions in a place.

Definitely would have been more logical that instead of taxing wool production in exceed, it was to come up with a sale price that would save them from excessive storage costs and not hold on to the same sales value for years. If you want to survive in a market, you should not err on the side of pride.

This case shows us that trade strategies can affect a local and even national sector. The prices of the wool market, must be obtained from the evaluation of costs, supply and demand, as explained by the course. In Colombia it happened between 2002 to 2006 a similar case, which was called the “Paper Poster”, in which the companies manufacturers, established a fixed market price for this product of the family basket. The financial superintendency of Colombia, discovered that there were no cost-standing costs and differential price balance, and only was sought to monopolize the demand. Economic sanctions exceeded 34 billion pesos. Today the regulation is still valid.

this case really amazed me i must say, i almost doubted if it actually happened, how can industries leaders and the AWC not understand the principles and laws of economics that governs all forms of trade? were they all illiterates? of-course that wasn’t the case cos there are many great businesses founded and managed by illiterates and school dropouts, this was a case of shear greed and pride and a typical example of “Pride goes before a fall”. in agribusiness it doesn’t matter the product, if success must be achieved, then the whole stakeholders in the entire value chain and elements of trade must be considered.This case happened in just 1990-91 and not 900-901BC, “obvious and determined stupidity” indeed. i like the fact that businesses are done in a more smarter and professional manner now and AWC can still bounce back if they really want.

This is serious case. I believed a lot of reexamination went on after their downfall and they learnt their own lesson taught by themselves. One single but simple mistake or ignorant can cause a whole havoc. What happened in 1990-1991 was really alarming how come they thought so and implemented that in marketing. Anyway its a lesson to all at a very high price

thank you my teacher

considering the fact that the AWC wanted higher prices for wool and was storing the wool in anticipation that the prices would increase. wouldn’t it have been better if they slowly release the stored wool to the market is small proportions so that the price for the commodity would be at a high price since the demand would have been greater than the supply

The idea with this sort of scheme is to buy and stockpile the product when prices are relatively low, and sell it when prices are higher. But the threshold prices you set for buying and selling wool need to be realistic. In this scheme, they were extremely unrealistic.

An important lesson to be learnt there, on what happens when people can’t admit they are wrong and keep trying to cling to their mistakes, there’s a quite a few who could take some classes in these COVID times of crazy schemes,

I bet this was so embarrassing to the cooperation. The forces of demand and supply in the market are very essential if one needs to stay in business. Ignoring one or both is the start of a journey towards losses and finally failure. Trying to manipulate one without doing a thorough analysis and projections will also result to losses upon losses.

I think putting price ceilings and floors is the best way to protect the interests of both the producers and consumers. Caring about the interests of just one party just can’t work.

Great content David,

In addition to setting a flooring price strategy, there is another annoying case of banning importation. Recently, the Nigerian govt lifted the ban on importation after sustaining this policy for over a year; this came after numerous outcry as a result of extremely high prices of basic food materials. Simple economics, the supply was low as local production could not handle the increasing demand for food, increase demand and low production leads to increase in the price of food materials. The effect of this policy is still been felt by the the poor, hopefully, with the lifting of the ban, price will stabilize in time.

Came here from Coursera. Appreciate the write up.

The write-up is so insightful. Thank you, from Coursera

Hi there. I’m taking the Cousera too that end up reading this wool case of Prof David.

What is reserve price? I guess I will understand the whole article after I finish your course in Coursera – Agriculture, Economics and Nature.

Is it similar story with BPPC (Badan Penyangga dan Pemasaran Cengkeh) of clove in 2008 in Indonesia?

A reserve price is the lowest price that the organisation will allow the product to be sold for. If the best price offered for the product is below the reserve price, the product is not sold. Instead, it is stored.

It’s incredible and frankly annoying such a blunder could be perpetrated by seemingly industry experts. Yet, from the comments and recent happenings, it seems like we haven’t learned much from it after all;

I’ve got some key takeaways;

Governments and policymakers must avoid interfering in market decisions to prevent an economic disaster like this in the near or far future.

Policymakers should be focused on creating an enabling environment to make the ag industry more attractive (e.g. investing in R&D) and leave the prices of agricultural products to be established by the forces of demand and supply.

Policies to benefit farmers must be as direct as possible, not built into decreasing input costs or increasing output prices. It has never been sustainable.

The knowledge of the supply and demand curve and market equilibrium will benefit producers and sellers far more than any price regulation scheme. Let the farmers decide what they want to grow based on data and not declarations/unrealistic speculations.

Though it’s easier for farmers to only identify themselves as “growers”, being indifferent to market dynamics and passing the risks down the value chain, this had ultimately led to misery as in the case of AWC.

Along with learning how to grow sustainably, modern farmers must also understand how the market works. Capacity building in this regard ensures the prosperity of the industry.

What a publication, I want to belief the so call reserve price should at the end be changed to scam price since the purpose to which it was made for could not be achieved and the debt or lost should be spread among the concerned parties with the producers who had thought would smile to the bank should bear the highest or greater percentage as well as the AWC who had failed to conduct a proper investigation and as well rejected the advise of the economist. In this regard, it is now cleared that dishonesty or insincerity always have its dead end result, If they had thought of the masses or the public, it is possible the lost would not have risen to that because as they produce they sell and the inventory on warehousing as well as tax and interest on credit facility at the bank would not have been accrue to what it end up to be. Equilibrium price and the market price could have settle it all, since there is alternative resources that can be used as against wool, that is away of adopting caution, the consumers would not want to incurred unnecessary cost in such a dicey situation. human projection at times may fail, but that was too stupid. when an absolutely wrong decision is taken without counting the cost with selfish mind-set it always a disaster. Finally, Government policies should protect both the farmers and the consumer and the middlemen should be checked through regulations.

thankyou Dr. Pannell for covering and explaining this topic on wool crisis.

It would be hard to imagine a more incompetent and irresponsible set of decisions than those of the AWC board and management throughout this episode. As a result they caused untold human misery. We can count the billions of dollars lost, but we don’t have statistics for the depression, the suicides, the fractured families or the agony caused to farmers by having to shoot and bury thousands of worthless sheep. I don’t think those responsible for this misery have ever been adequately held to account.

The wool industry has never recovered. It remains a shadow of its former self.

A really basic understanding of economics would have avoided all of this. Not only did the industry leaders lack this understanding, but, as Massy reveals, they actively resisted and rejected advice from competent economists when they received it, including economists who worked for them.

It’s unfortunate to experience that governments who came to power through undemocratic means, always find it difficult to leave power easily, so one of the way to maintain their lust for power is by imposing policies which to many might appear as supportive however with long term social economic disadvantages on the livelihood of the citizens. Meaning unsustainable.

Raising up the price of any good beyond the market price will not only compromise quality of the product produced, but also in the future causes causes insurgencies which may occur demanding for same policies which when current governments have been replaced with another one with different policies. This revolts might be intense to the extent of causing widespread economic crises worse than before, would the later governments fail to fulfill the demands of the majority population who are mainly farmers.

an interesting demand and supply model how it can made price fluctuation around its movement. in market equilibrium price can be rotated around it, due to demand and supply model as it illustrates in the panel reading about wool production and its market in Australia.

This article has really been of help, wisdom is profitable to those who seek it and use it.

When one is greed for gain, all that matters is oneself. The greedy party care less about others. It is nothing bad, having the farmers in mind and wanting to favour them but it is also important to consider all other parties involved and the effect of the policies planned, on everyone. If they had considered all equally, that might have avoided them the great loss. I will state that the people/consumers should be given consideration just as the producers, so we can have optimum prices.

The American Pork Industry seems to be going through the same problem with supply and demand.

SYLVIA JARRUS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL says:

The American pork industry has become so efficient that demand can’t keep up with supply. In search of solutions, farmers and processors are looking at everything from new overseas markets to fattier, tastier pigs.

The American pork industry has a problem: It makes more tenderloin, ham, sausage and bacon than anybody wants to eat.

From giant processors to the farmers who supply them, they are in a predicament largely of their own making. They made production so efficient that demand can’t keep up with supply. Their long-running advertising campaign touting pork as “the other white meat” was remarkably effective at reaching consumers—but wasn’t actually the best way to market the product, some in the industry now argue, because it drew a direct comparison with chicken, which is typically more affordable. She goes on to say that American’s don’t eat enough pork.