372. The fairness of additionality rules

At a national soils workshop on 5 May 2022, two speakers commented on the additionality rule for soil carbon offsets, saying that the rule is unfair and causes concerns amongst some farmers. How unfair is it really?

Under the Emissions Reduction Fund in Australia, farmers can get paid for sequestering carbon in their soil. 13 ways of sequestering soil carbon are recognised in the policy, including: switching from cropping to permanent pasture, changing grazing management to promote soil vegetation cover, retaining stubble after a crop is harvested, and converting from intensive tillage to no-till.

The idea underpinning this policy is that paying farmers will incentivise them to adopt these practices that sequester carbon in the soil, contributing to a reduction in climate change.

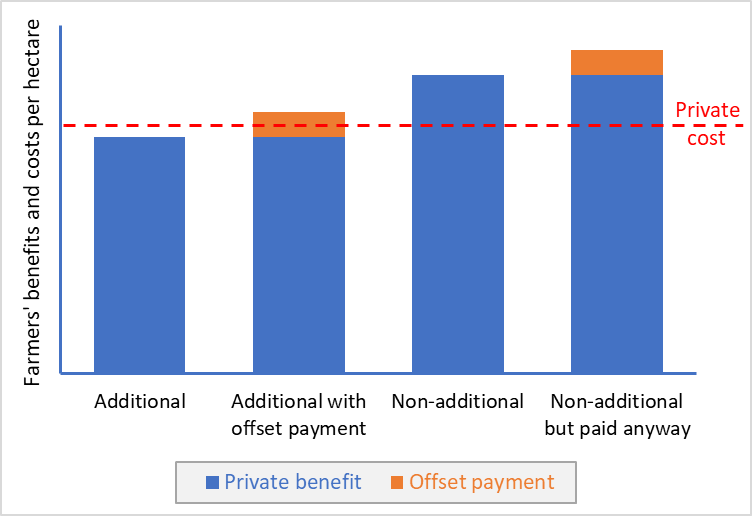

Additionality refers to whether a payment results in additional actions that would not have occurred without the payment. In the figure below, the first bar shows a situation where the farmer’s private benefits from adopting a sequestering practice are not large enough to exceed their private costs of adopting it so no adoption occurs, but with an offset payment, the overall private benefits are large enough to outweigh the private costs (the second bar), so the farmer adopts the practice.

Non-additionality means that the farmer would have done the action even if they were not paid because the private benefits exceed the private costs (the third and fourth bars in the figure). In that situation, a payment does not cause any additional action and so does not contribute to addressing climate change. Logically, if we seek to make the biggest possible difference to climate change for any given cost, we should avoid making offset payments for non-additional actions.

This particularly matters because some of the allowable ways of sequestering soil carbon are non-additional for most farmers. Almost all crop farmers use no-tillage methods these days, so paying all farmers who use no-till would result in a big cost to society but make almost no difference to climate change. It would use up resources that could be used in other ways to make a bigger difference to climate change.

In that light, would it be fair for all farmers who use no-till to receive offset payments irrespective of additionality? I expect it would not seem fair to the general public who probably have expectations that a climate-change policy should address climate change.

However, fairness is in the eye of the beholder. In Australia’s soil carbon policy, any farmer who is already using a particular sequestration action is deemed to be non-additional for that action. Applying this additionality rule means that some farmers will receive money for doing a particular action (the ones who start using it after they sign up for offset payments) but others will not (the ones who were already using it before the policy started). Is that fair? From the perspective of the farmers who are not receiving payments, perhaps not. Some farmers who adopted the practices early see themselves as being disadvantaged as a result of having been more socially responsible. They have done the right thing voluntarily, but others who have dragged their feet are the ones getting paid.

But even in this scenario, the fairness question is not straightforward. The farmers who have adopted the soil-sequestering practices have probably done so because they believed that there were benefits to themselves in terms of farm productivity (bar 3 in the graph). Listening to people who are enthusiastic about soil carbon, they usually emphasise that the private benefits are large. But people and farms are heterogeneous and any given action would not produce benefits in excess of costs for everybody. The people who have not adopted may have made a judgment that the benefits to them are less than the costs (bar 1).

Viewed in that light, why should it be considered unfair to pay the non-adopters enough to make the practice attractive enough to adopt? If the payments are not excessive, the recipient farmers would not be made better off than the unpaid existing adopters because the existing adopters already get a private net benefit from adopting, whereas the non-adopters expect to make a net cost from adopting. The payments to non-adopters are just making up the shortfall in benefits to make adoption worthwhile. The payments don’t generate big profits – they are covering other costs plus a small profit margin (bar 2). For existing adopters, any payments they receive are all cream on top of the cake because they already make positive net benefits from adopting (bar 4).

Viewed in that light, why should it be considered unfair to pay the non-adopters enough to make the practice attractive enough to adopt? If the payments are not excessive, the recipient farmers would not be made better off than the unpaid existing adopters because the existing adopters already get a private net benefit from adopting, whereas the non-adopters expect to make a net cost from adopting. The payments to non-adopters are just making up the shortfall in benefits to make adoption worthwhile. The payments don’t generate big profits – they are covering other costs plus a small profit margin (bar 2). For existing adopters, any payments they receive are all cream on top of the cake because they already make positive net benefits from adopting (bar 4).

Whether offset payments to farmers are fair when comparing farmers depends in part on how well additionality is assessed in the policy. If the assessment of additionality is weak and allows payments to some farmers who would have adopted anyway, there is a legitimate fairness issue because some non-additional farmers are getting paid (bar 4) and some aren’t (bar 3). Australia’s policy approach of judging additionality solely on whether farmers are already doing the practice means that we will inevitably end up paying some non-additional farmers; specifically, farmers who have not adopted the practice yet but would have done so in future even without an offset payment.

Weighing all that up, there are a few potential ways forward.

- We could declare that all users of a practice are eligible for offset payments irrespective of additionality. This would reduce unfairness amongst farmers but I think most people would feel that that approach is not fair to taxpayers or to people concerned about climate change.

- We could try to improve the measurement of additionality so that all non-additional payments are avoided. That would mean that we avoid unfairness between different farmers for whom payments would be non-additional. Maintaining an additionality rule would not conflict with fairness between the additional and non-additional cases, because the payments are covering costs (including opportunity costs) incurred by additional farmers, rather than enriching them. Unfortunately, assessing additionality accurately is extremely difficult because it depends on predictions of farmers’ behaviour in hypothetical scenarios. Even if policy makers wanted to improve it, it isn’t obvious how best to do so.

- We could carry on with the existing system for assessing additionality. Although farmer-to-farmer fairness looms large for a minority of farmers, from a broader perspective it is less of an issue when you think about farmers’ private benefits and costs of adoption, as in the figure above.

- We could abandon any system of offsets for soil carbon. That would avoid all the issues related to unfairness described above.

If we have a soil-carbon offset scheme, including within it a system for additionality is not a cause of great unfairness in the farming community. But if it were possible to improve our assessment of additionality, that would have multiple benefits, including a small improvement in farmer/farmer fairness and a larger improvement in farmer/taxpayer fairness.

On the other hand, there are many other problems with soil carbon offsets (see PD 371) and some them are more serious than the fairness issues. For those other reasons, the best option, in my view, is the last one. If we removed soil carbon from the Emissions Reduction Fund, we could reallocate the resources onto other ways of combating climate change that would make a far bigger difference.

Webinar: “Could soil carbon sequestration ever be a worthwhile climate policy?”

I presented the Environmental Policy Lecture supported by AARES, CEEP and CAED

Date: Friday 20 May 2022

Time: 11:00am – 12:00pm AWST

To view a recording for the webinar, download the slides and read the Q&A session, go to Pannell Discussion 374.

Further reading

Pannell, D.J. (2022). Challenges in making soil-carbon sequestration a worthwhile policy. Pannell Discussion 371.

Readers may be interested in knowing that soil scientists are among those who consider the potential for farmland soil C sequestration unlikely in Australia; eg: Sanderman, J; Farquharson, R and Baldock, J. 2010. Soil carbon sequestration potential: A review for Australian agriculture. Urrbrae, S.A.: CSIRO; https://doi.org/10.4225/08/58518c66c3ab1. AND – Lam, S.K., Chen, D., Mosier, A.R. & Roush, R. The potential for carbon sequestration in Australian agricultural soils is technically and economically limited. Sci. Rep. 3, 2179; DOI:10.1038/srep02179 (2013). Scientists in other countries have also expressed doubts on programs for farmland soil carbon sequestration, even in more temperate regions with soils of higher inherent fertility: -eg: Amundson R. and Biardeau L. 2018 Soil carbon sequestration is an elusive climate mitigation tool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, (46) 11652–11656 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1815901115.

Thanks Ann.

Unfortunately the additionality rule provides perverse incentives because it is better to have poor practice so you can improve it or even to go backwards so you qualify. You can greatly increase below-ground sequestration by not clearing land or revegetating it. One way to achieve this is to use land more efficiently. Unfortunately, current C accounting methods don’t encourage this be not properly including land use.

That’s not a problem with additionality in principle, but it is a problem with the way that the additionality is assessed in Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund (based on what people are doing in a baseline period prior to adopting the new carbon-sequestering practice). My guess would be that the amounts of money at stake are not high enough to motivate many people to behave in that way, but there might be a bit of it.